Etched in Memory: The Artwork of Vincent Colyer

Following the Bombardment of Wrangell, Vincent Colyer published detailed artwork of Fort Wrangel and Ḵaachx̱ana.áakʼw which challenged the Army’s version of events.

Colyer’s Trip to Alaska

Vincent Colyer was a hero of the American Civil War—not for fighting, but for his compassion. As a devout Quaker, Colyer refused to take up arms and instead dedicated himself to helping the dead, dying, and wounded. After the war, President Grant appointed him to the Board of Indian Commissioners, where he served as Secretary and traveled out West. Colyer not only documented the conditions of Indigenous life but also brought his reports to life through detailed artwork that helped convey the reality to leaders in Washington, D.C.

In October 1869, Colyer was sent to Fort Wrangel, Alaska to investigate accusations that the Army was responsible for debauching and demoralizing the Indigenous. Colyer visited every home in the village to conduct a census of the men, women, boys, and girls. During his visit to Ḵaachx̱ana.áakʼw, he aided a Tlingit man who had been severely beaten by U.S. soldiers and personally witnessed an attempt to smuggle liquor from a steamship. In his confrontations with the post’s commander, Lt. William Borrowe, Colyer found the commander to be dishonest, evasive, and unconcerned with the welfare of the Tlingit. In fact, Lt. William Borrowe had a reputation for dishonesty that started before, and continued after, his time in Alaska.

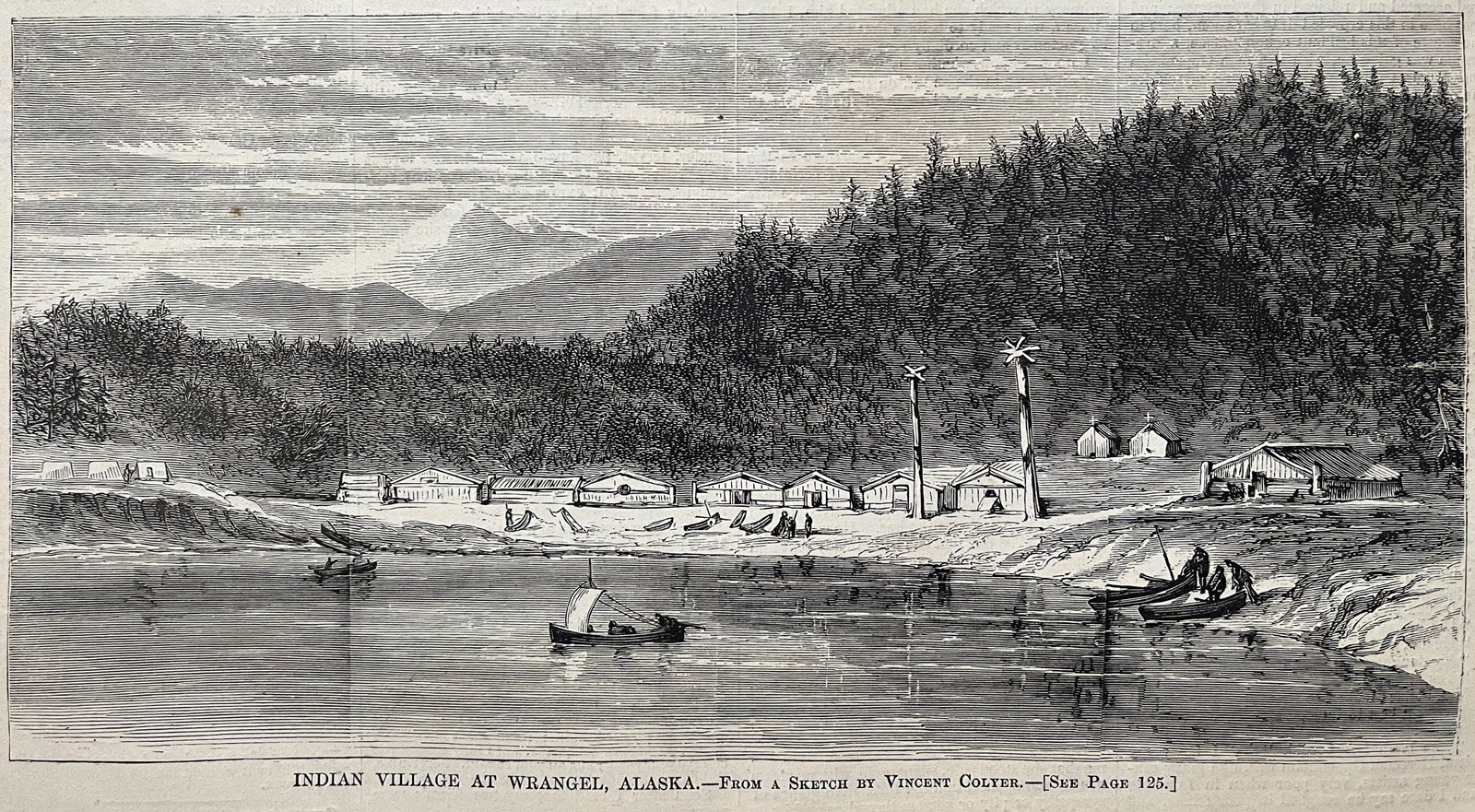

Before Colyer left Fort Wrangel, as he did wherever he traveled, he created detailed paintings of the landscape and daily life. His artwork provides a rare glimpse into Ḵaachx̱ana.áakʼw before the rapid changes of the 1870s. Along with photographs by Eadweard Muybridge in 1868, these images are among the earliest known depictions of Wrangell's history.

Bombardment of Wrangell

Two months after Colyer left Fort Wrangel, Lt. Borrowe hosted a day-long, drunken Christmas party inside the fort. Late at night, a Tlingit guest bit off the finger of a white woman, for which he and his brother were shot. In retribution, their Tlingit relative shot and killed post-trader Leon Smith. In the morning, when the village leaders failed to find and hand over Smith’s killer, Lt. Borrowe ordered Ḵaachx̱ana.áakʼw fired upon for two days until Smith’s killer surrendered and was hanged.

The first reports of the bombardment appeared in newspapers down the west coast, and many simply echoed the reports from Lt. Borrowe and Lt. Loucks. But Vincent Colyer was not buying it.

Though his time in Alaska was short, Colyer gathered enough evidence to confirm the Army’s debauchery. He personally witnessed liquor coming in, and he saw the first-hand effects of violence used against the Tlingit. He possessed detailed letters from independent eyewitnesses citing examples of the Army’s abuse of Alaska Native people. There was enough to confirm the worst rumors were true.

With Fort Wrangel still fresh in his memory, Vincent Colyer looked for something to capture the public’s attention. Among his papers were plenty of stories, but one piece of his collection told a story without words: his paintings. His serene scenes of idyllic life along peaceful shores conveyed a sense of beauty and dignity. They challenged the Army’s depiction of the village as a threat.

Harper’s Weekly

To ensure the public saw these images, on February 19, 1870, Colyer published a full-page spread in Harper’s Weekly, a popular magazine. In a short column accompanying the artwork, Colyer publicly criticized Lt. William Borrowe for the bombardment:

“Mr. Colyer explains that the village was only about 500 yards from the post, of which we give an engraving, and as there were not over seventy-five able-bodied men in the village, it is certainly remarkable that the commandant of the post, who had a company of well-armed soldiers under his orders, should resort to bombardment, instead of taking a squad of men and making arrests. The villagers, Mr. Colyer thinks, will now be afraid to occupy their houses again for the winter, and will be great sufferers by this act of the commandant...”

One month following the publication of Colyer’s images in Harper’s Weekly, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution in March 1870 requesting a report from the Secretary of War about the bombardment. Having established himself as an expert on the subject, Vincent Colyer was assigned the responsibility to write the report. One month later, in April 1870, Congress had its answer: The Colyer Report. The document included the Army’s official reports, alongside Colyer’s scathing rebuke, examples of what he witnessed, and copies of letters from eyewitnesses. On the cover, and inside the report, Colyer reprinted his etchings Harper’s Weekly.

The Artwork

Sketch No 1: KaachXana.áakʼw

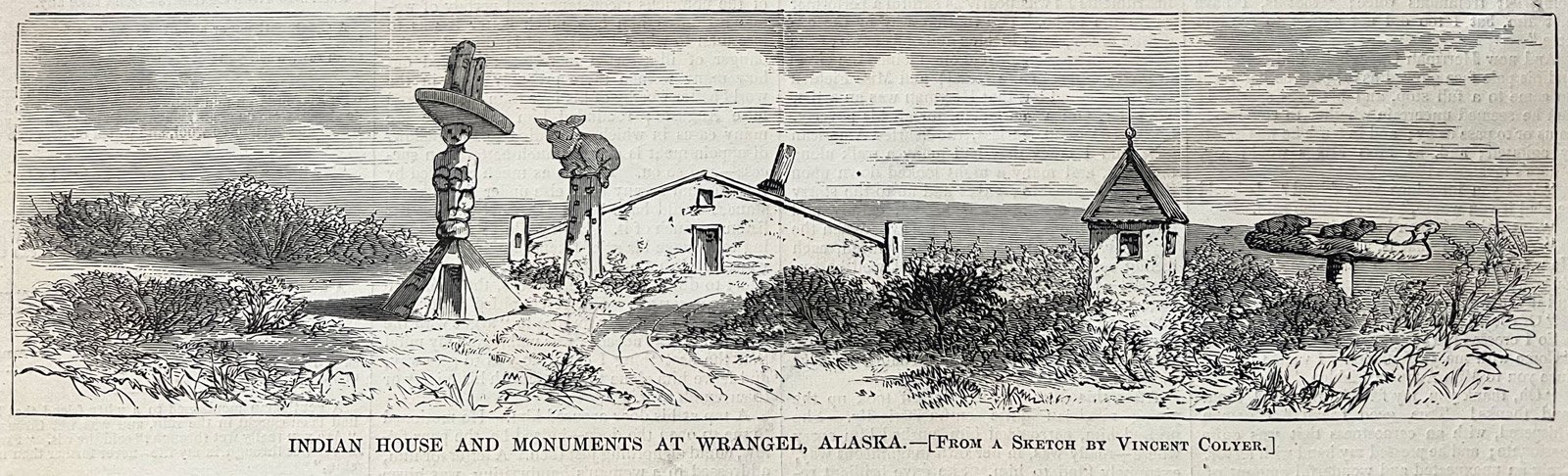

“In front of most of the cabins of the chiefs, large poles, elaborately carved, with figures imitating bears, sea-lions, crows, eagles, human faces, and figures, are erected. These are supposed to represent facts in the history of the chiefs, as well as being heraldic symbols of the tribe. By referring to picture No. 1, you will see the poles (very poorly engraved) standing in front of the cabins; in another sketch not engraved is a large copy of these poles, and on No. 5 are some very curious colossal frogs, a bear, and war-chief, with his “big medicine-dance” hat on. All of these things show a great fondness for art, which, if developed, would bear good fruits. It also shows that these Indians have the time, taste, and means for other things than immediately providing the mere necessities of existence.”

In Harper’s Weekly, Colyer described this illustration as showing “the portion of the village recently bombarded, which is located on the bay nearest the United States post.” Colyer described a “well-built village” of thirty-five houses constructed from hewn timber, 30 by 50 feet, and inhabited by 450 men, women, and children.

Harper’s Weekly remarked, “The village, as our engraving shoes, was beautifully situated on the shore, within the edge of the forest, with a magnificent back-ground of mountains in the distance. The inhabitants were quiet, honest, and well-disposed toward the whites, and it is very much to be regretted that the commandant of the post should not have been more judicious in his treatment of them.”

Sketch No 2: Fort Wrangel

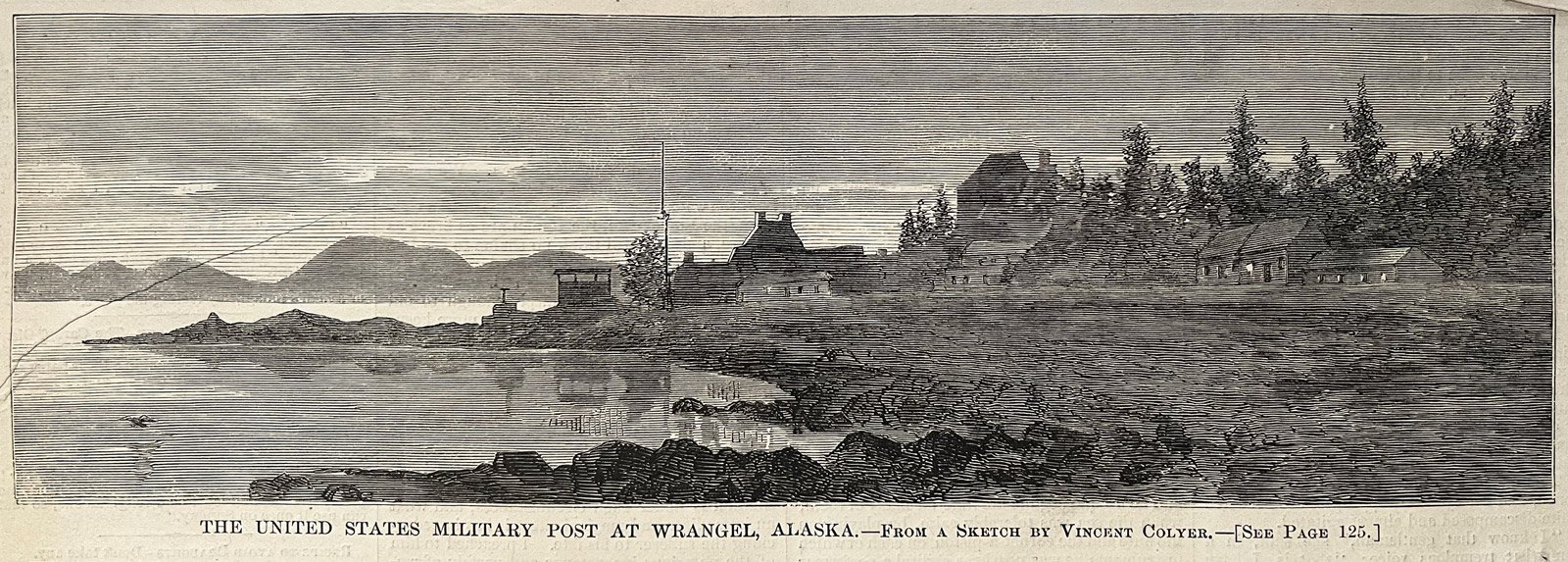

“...A rapidly engraved sketch of the government post on which the guns are located... The right of Sketch No. 2 joins on the left of Sketch No. 1, and as seen thus shows the narrow cove across which the shelling of the village took place. The small log-house and bowling alley to the right on Sketch No. 2 is Leon Smith’s, the post-trader’s store.”

In contrast to the sunny, open spaces in Colyer’s other illustrations, this one is dark and flat. The angular silhouette of Fort Wrangel’s skyline stands against the dim skies, with shadowy buildings in the foreground. To the right, Colyer drew the log cabins operated by Smith & Lear as a trading post and bowling alley. Colyer collected a letter from Leon Smith and was shocked to later learn that Leon Smith was mortally wounded in front of his store before the bombardment.

Sketch No. 3: Skillat’s House Front

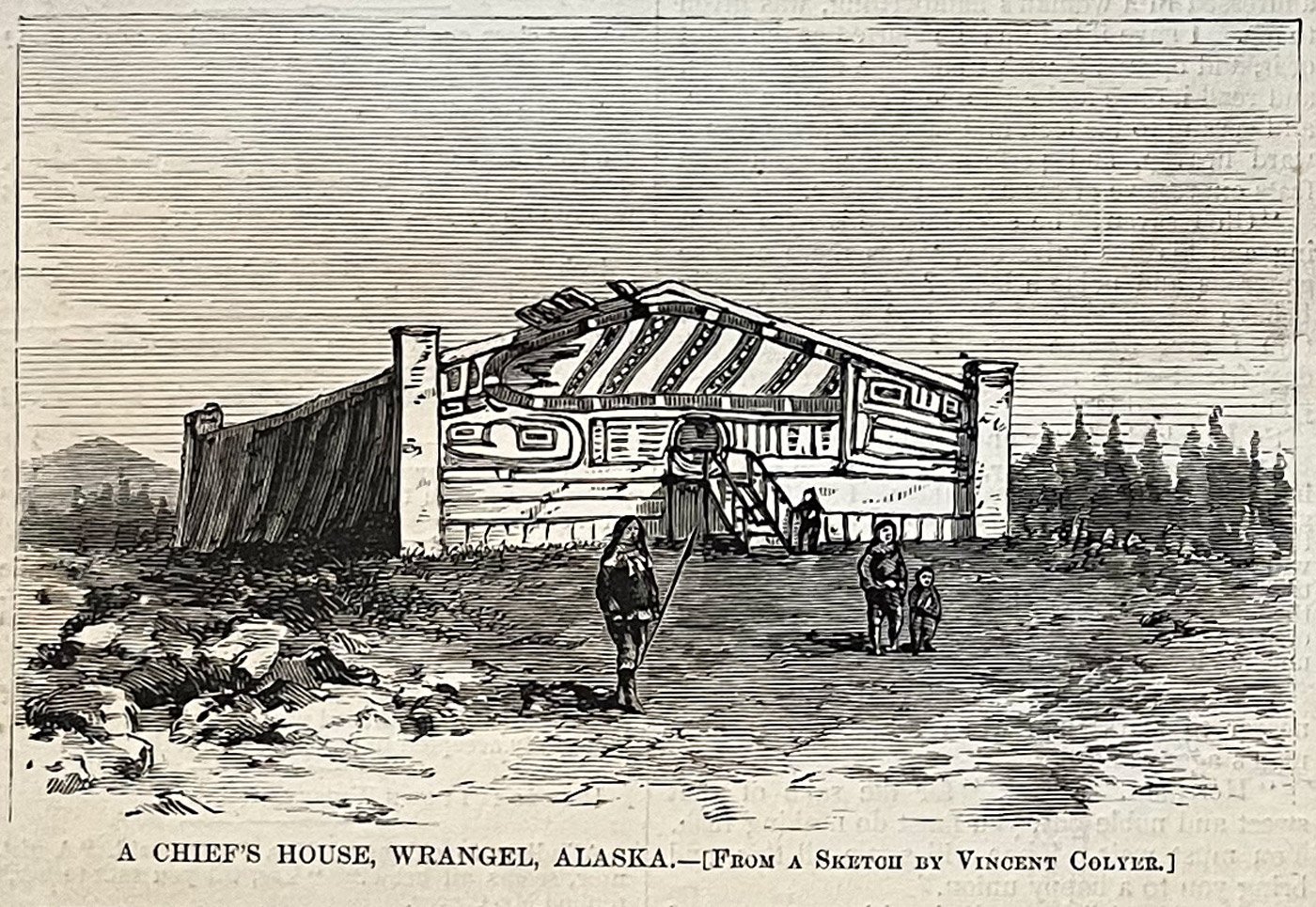

“Some of these Indian houses are quite elaborately painted on the front, as seen in Sketch No. 3, the residence of Skillat’s widow. These paintings have an allegorical meaning, and frequently represent facts in the history of the chief or the tribe. In front of the entrance there is usually a porch, built with railing, to prevent the children from falling off, and you will notice the round hole for the entrance. They are covered inside with heavy wooden doors, securely fastened within by large wooden bars, as if for safety against attacks. The doors are usually about four feet in diameter, and their circular form resembles the opening of the ‘tepé’ or tents of the tribes of the plains.”

This image served as the cover of The Colyer Report. In the report, Colyer described this as “the residence of the widow of Skillat, the old chief of the Stikine tribe at Wrangel.” Harper’s Weekly commented, “Our sketch of the house of the Indian chief shows the style of architecture employed in the better class of dwellings in the village. It belonged to a chief named Skillat, and at the time of the bombardment was occupied by his widow. The front is curiously ornamented with paint and rude carving.”

Sketch No. 4: Inside Skillat’s House

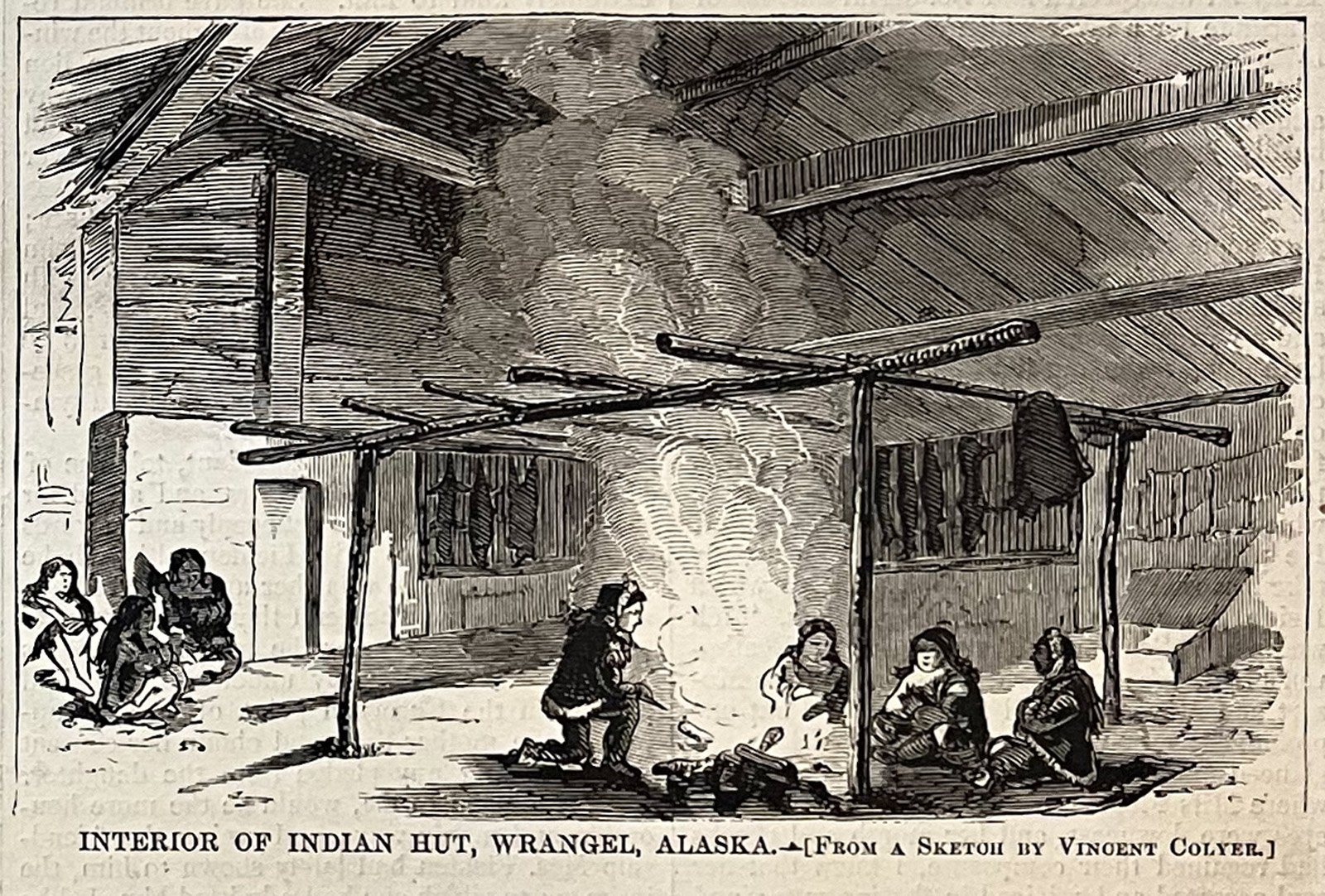

“These cabins, or private sleeping-rooms of one family, are seen in Sketch No. 4, built on raised platforms. They are as neatly finished as most whaling ships’ cabins, and have bunks, or places for beds, built on the inside around the sides. They vary in size, being usually about ten by twenty feet, with ceilings seven feet high. Some of the young men are quite skillful mechanics, handling carpenters’ tools with facility, and if you will closely examine the sketch you will see that there is a floor and raised platform of boards, neatly fastened together, below the private cabins or rooms spoken of, so that the amount of carpenter work about one of these houses is considerable. They have a large opening in the roof, through which the smoke of their fire passes, as seen in No. 4. Usually, this opening in the roof is covered with loose boards, which are placed on either side of the roof, according as the wind may blow, always with an opening left, through which the smoke passes out. Sometimes they build a large wooden chimney, like a cupola, over this opening, but more commonly it is only covered with boards as described. You will notice in Sketch No. 4 a frame-work erected in the center of the cabin. On this rack of untrimmed sticks they hang their salmon and other fish to smoke and dry them over the fire. They then pack them for use in square boxes neatly made of yellow cedar, smoked, oiled, and trimmed with bears’ teeth, in imitation of the nails we use on our trunks—like old brass nails of former years.”

Sketch No. 5: Shakes Island

“In the vicinity of the house [of Skillat] belonging to the principal chief, who bears the name “Shakes,” are various carved objects of grotesque shape and rude workmanship, which are shown in our engraving. One of these figures is that of a bear reposing on a stump, the holes in the sides being supposed to represent his tracks. On the platform on the right of the picture rest the figures of three colossal frogs. The small building near the platform is a burial-place or tomb.”

Vincent Colyer visited Shakes Island, home of the Naan.yaa.áyi and their hereditary clan leader, Shakes. While his perspective is from the front of the house, he is set far back and below the horizon, likely on the north shore of Shakes Island. This low perspective causes the totems in front to appear taller than the building, while the mountain range in the background appears beneath the building’s peak.

Lt. Borrowe described his December 27 assault on Shakes Island, saying “after four shells had been fired, two bursting immediately in front of the houses, and two solid shots just through the house of the principal chief, Shakes, a flag of truce was seen approaching the post, and firing on my part ceased.” In his report, Colyer included this “picture of Shek’s house, through which a couple of six-pound solid shot were thrown.” This was another instance where Colyer’s ability to illustrate paid off, as he had documentary evidence of places included in the bombardment story.

Impact

Artwork from color-free versions of Harper’s Weekly.

For most Americans, Colyer’s feature in Harper’s Weekly was the first time they heard of a place called “Wrangel.” The Treaty of Cession with Russia was barely two years old, and Alaska was still shrouded in mystery. The images may have surprised people. This was not verdant farmland, it was all rocky coastline and steep hills. Despite having hardly any settlers, the Army paid for a large fort with officers and a detachment of soldiers. It called into question the Army’s purpose. Who were they there to protect? And from what?

One month after Congress and the President received The Colyer Report, the Army announced it would abandon Fort Wrangel and its other Alaskan posts, except for Sitka. The Colyer Report hastened the demise of the Army’s first attempt to control Alaska.

Vincent Colyer’s power was not just in his words. His ability to communicate visually helped to draw attention to his cause and brought humanity to the subjects of his artwork.

If you’d like to learn more, check out our Bombardment of Wrangell page for more details, resources, and visuals.